This text by CAROLINE SECK LANGHILL is published alongside BARBARA BALFOUR‘S Living & Dying exhibition.

Text and Perception in Living & Dying

by Caroline Seck Langill

The sixties are endless. We still live within them.1

PAMELA M. LEE

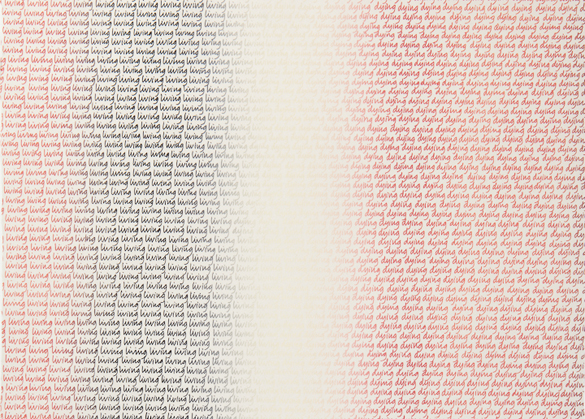

Barbara Balfour’s recent body of work haunted me in unusual ways since I began to contemplate its meaning for this essay. Memories of the era, of my own coming of age resurfaced and implicated themselves as part of the extended cognitive system I was drawing upon in order to consider these canny lithographs. On first viewing, this series of prints with their pulsing blurred stripes referenced the faded colour fields found across media, from the street to the gallery, during the 1960s. The bands of colour vary from a psychedelic spectral range to a more consistent patterning which fades betweenthe chosen colour of ink to white, and back again, giving the text printed with paler inks a ghostly glow. At closer proximity the stripes disappear in favour of two words: living, dying. Each line repeats living living living living and then at roughly half the distance of the width of the paper, the words switch to dying dying dying dying. Each word is distinct. Each line is distinct. But viewed together from a distance, in their tight juxtaposition, the combined effect generates a cohesive typographical field with waves of colour and light. The words hold and bind the ink to the page, they pulse with the frequency of the colour they transmit, so that the illusion is not just clever, but is also physiological. Our rods and cones and our emotions are piqued, as the words are relentless in their evocation. A subtle plaid of colour and text is produced between them, implying the weaving of the two; the warp and weft of life and death.

If we are to assume Pamela Lee’s observation of the endless sixties to be true, then it is not surprising that these works hearken back to that period. Living & Dying speaks to the present from the past in the way the works in the exhibition sit between two eras informed by technology in new and surprising ways. It is not just the formal aspects of these works that take me back however, but also the text and its handling by the artist. Considering the argument thus far, it makes some sense to leapfrog over text-based works of the 1980s informed as they were by structural and semiotic imperatives, and instead consider the conceptual and durational works of Ed Ruscha and On Kawara. Ruscha’s faded colour fields and landscapes overladen with slogans have some bearing on Balfour’s works since they locate and appropriate the aesthetics of dip-dyed street wear for purposes of fine art. In the late sixties, Seth Siegelaub organized exhibitions of Ruscha’s and Weiner’s work adhering to his mandate to focus on printed matter, its form and process of distribution. The simultaneous withdrawal from the field of the visual and a staging of that withdrawal as a form of spectacle, was a paradox integral to the works in question.2 Balfour’s works are similarly strange. They are unsettling in their ability to play with our eyes and our mind as the words come and go with distance. They are also distinct from the aforementioned works of Ruscha’s and Kawara’s where the focus was on language and its reference to everyday events and objects. So perhaps we need to go a bit further back to find a peer for Balfour. Bridget Riley, a British painter working in the early 1960s was, the reluctant heroine of this sixties phenomena. 3 For her optically arresting paintings Riley depended on the retinal response, as does Balfour with this series, where the marks on the page dots for Riley, words for Balfour craft optical tricks. Pamela Lee sees a fetish of visuality in Riley’s paintings that suggests a reading of the body under the conditions of a shifting technological culture and how the time of that body speaks to the repressive consequences of a burgeoning technocracy. 4 Well the technocracy is no longer burgeoning; it has arrived, and we are complicit in our embrace of it.

We have hurdled forward, to a post-millennial culture where analogue and digital media fight for legitimacy, and relational practices signal the ultimate dematerialization of art. These polarities of media, more integrated than anyone cares to admit, make Balfour’s decision to approach her text and its production all the more surprising. In his Today Series, On Kawara hand painted the text, emulating machine-made sans-serif type. As with Kawara’s work, it is not in order to legitimate the labour that Balfour takes a handwritten approach to her matrix, but to emphasize embodiment. In previous works Balfour actually used software that formatted her own handwriting to generate a signature font, but she eschews this method here, favouring unpredictability

and chance.

As our eyes adjust their focal lengths to the words or the stripes, we move in and out of our connection to living and dying. Our secular culture has created a situation where we are unable to respond to these two states with any certainty. Death surrounds us in popular culture, fundamentalism proliferates in sectors of virtually all world religions, and the children of the sixties are approaching their senior years. Susan Sontag states: Every era has to reinvent spirituality for itself. 5 Having channeled the sixties in order to emphasize her idea as a machine that makes art 6, we are confronted with the meaning of existential questions surrounding living and dying, questions grappled with by conceptual artists in the sixties. Balfour’s beautiful and haunting series Living & Dying boldly re-joins this company with two words and her master printer’s hand, connecting the concerns of that era to our present worldview.

CAROLINE SECK LANGILL is a Peterborough-based artist whose practice encompasses visual and new media art, curatorial projects and scholarly writing. Over the past decade, she has pursued research pertaining to the intersections between art and science as well as in the related fields of new media art history, criticism and preservation. Presently, she is an associate Professor in liberal Studies at OCaD University where she teaches courses revolving around technology and digital culture.